A few years ago, Glenn Hart of Houston-based Laredo Energy said he was ?kind of enamored? of the Eagle Ford Shale.

The company in 2009 had started drilling exploratory wells on 130,000 acres north of Laredo, and Hart's attitude about the other geologic bands of rock that lie atop the Eagle Ford was this: They were standing between him and the Eagle Ford and needed to be drilled through quickly to get to the real payday.

Then a geologist came into Hart's office with data that indicated that some of those other formations had as much potential as the Eagle Ford.

Hart was skeptical. ?I basically said, ?Get out of my office.'?

But the geologist was right.

For Hart and others, the Eagle Ford isn't just about the shale formation anymore.

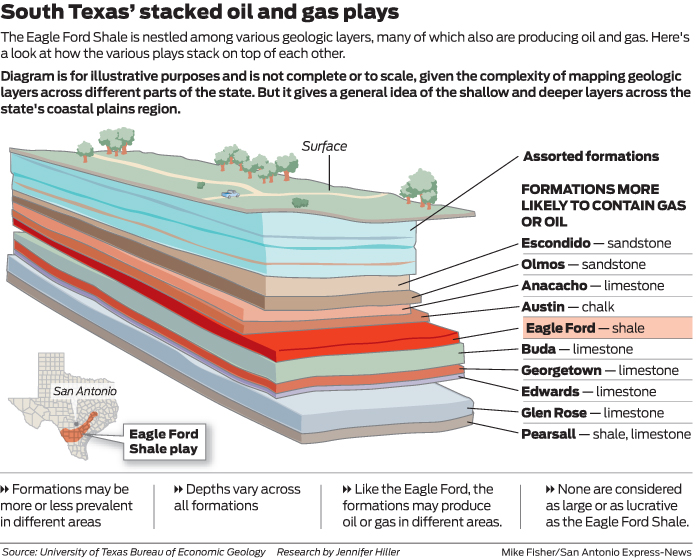

There's an increasing amount of drilling in the layers above and below the South Texas shale play, which has emerged among the hottest fields in the nation for oil and gas production. The Eagle Ford is a 50-mile-wide swath of shale that runs from the Mexican border to East Texas, and 4,970 wells have been permitted in 25 counties.

While the Eagle Ford appears to be the mother lode ? the largest and most consistent South Texas formation holding the most oil and gas ? there are at least 10 other rock layers sitting above or below it that also are producing oil or gas.

This has the oil and gas industry returning to some old friends ? formations such as the Austin Chalk and the Olmos Formation ? that for decades have produced using traditional vertical wells. Now, the industry is applying new horizontal drilling techniques with success.

Laredo Energy so far has drilled wells in six geologic layers on its acreage: the San Miguel Formation, Navarro Group, Wilcox Formation, Olmos, Escondido and Eagle Ford. And two-thirds of its production is coming from outside the Eagle Ford Shale.

?This is not just a local phenomenon for us,? Hart said. ?It's starting to become widespread.?

Peggy Williams, editorial director with Hart Energy, said horizontal fracturing techniques are being used not just for shale, but in other rock such as sandstone, chalk and limestone.

?What's happening is these technologies to extract oil and gas from tight formations like shale have been developed to the point where they're fairly effective,? Williams said.

It's early in the exploration phase of these other formations, so it's hard to make generalizations.

And even with production rising in the Eagle Ford, estimates for what that field will produce vary, so there's not comparable production data for these newer plays.

But drilling in these other layers has started to change the way some mineral leases are structured in South Texas and has prompted some oil and gas companies to try to lease in deep formations that haven't been tapped.

Eric Potter, associate director in the energy division of the Bureau of Economic Geology at the University of Texas at Austin, said that even with a century of production in Texas, trying to figure out which formation will yield gas or oil ?gets complex in a three-dimensional way.? It takes the industry actually drilling and producing to figure out what a certain area might yield.

?This is like one vast experiment being conducted. Some people call it the Braille method,? Potter said. ?We don't know what the ultimate production from these formations is going to be.?

Opportunities vary

These other formations generally don't appear to be as large, as profitable or as consistent as the Eagle Ford. And they're not stacked tidily like a layer cake. A formation that's thick in one county might be barely present in another.

The Eagle Ford generally produces more oil on its northern arc, more natural gas to the south and natural gas liquids in the middle. Similarly, these other formations in some areas might produce dry gas, but in another area, the same formation might provide a bonanza of profitable crude oil or natural gas liquids.

That explains why people across South Texas are hearing plenty of rumors about which geologic layer is the next big find.

?Someone may talk about the Olmos. Another person may talk about Escondido. Someone else may talk about the Pearsall,? Williams said. ?These secondary objectives might become significant producers.?

One example of a non-Eagle Ford success: Houston-based Escondido Resources II, which holds about 60,000 acres in the shallow Escondido and Olmos sandstone formations in Webb, La Salle and McMullen counties, has an Escondido well producing 1,000 barrels of crude oil per day.

A report this summer from information and analytics company IHS Inc. pegged the Eagle Ford Shale as having a flow of 300 to 600 barrels a day of oil and oil-rich liquids, based on average well production in a peak month.

Rusty Shepherd of Momentum Oil & Gas LLC said the company has spent most of 2012 leasing acreage in formations that run deeper than the Eagle Ford, including the Edwards, Glen Rose, Pearsall and Salado, and is concentrating in the so-called ?Four Corners? area, where Frio, Atascosa, La Salle and McMullen counties meet.

Shepherd is particularly interested in the Pearsall, a shale and limestone formation that holds a mix of crude oil and natural gas. Hart Energy's Williams thinks the Pearsall is the shale layer most like the Eagle Ford.

The Pearsall long was assumed to produce only natural gas until 2011, when Oklahoma-based Cheyenne Petroleum Co. drilled a well that started producing crude oil, Shepherd said.

Momentum estimates that there are 17 Pearsall wells now, and it plans to start drilling in the formation next year.

?It's definitely a new look at an older play,? Shepherd said.

Leasing

Petrohawk Energy Corp. drilled the first of the Eagle Ford wells in 2008 in La Salle County, setting off a frenzy of leasing activity across South Texas for three years.

Attorney John Petry, a shareholder with Langley & Banack in Carrizo Springs, said that as the Eagle Ford play has developed and people learn more about other formations, some mineral owners have gotten specific in their contracts, stipulating how deep a company can drill or even into which formations.

?Some of the ones I'm negotiating only go to a certain depth,? Petry said. ?(People) will say, ?We won't give you the Buda. We won't give you the Edwards.' Many of the landowners are reserving certain things.?

Because so much South Texas acreage is tied up in leases already, it's difficult for companies to enter the Eagle Ford ? or anything above or below it ? at this point.

But Bill Deupree, CEO of Escondido Resources II, said it is possible. ?There's still leasing to be had,? he said. ?The landowners want to make sure that all of their minerals get developed.?

Allen Howard, president and CEO of NuTech Energy Alliance, a company that analyzes wells and reservoirs around the world, likes the Austin Chalk, Escondido and Olmos formations, partly because they're shallower ? and cheaper ? to drill.

Deupree said that because of the shallower depth, his company saves between 40 percent and 60 percent on drilling a well in the Escondido or Olmos. Depending on depth, an Eagle Ford well can cost $7 million to $10 million to bring into production, he said.

?We were here before the Eagle Ford was discovered,? Deupree said. ?The Eagle Ford underlying the Escondido and Olmos was a huge bonus. But our focus is still the Olmos and Escondido.?

The Buda Limestone is a deeper layer, but Howard said it's oil- or gas-bearing depending on location. On the north side closer to San Antonio, it has more oil.

Hart, CEO of Laredo Energy, said drilling in other South Texas formations means that one of the industry's major challenges already is solved: The pipelines and roads to large, remote ranches already will be in place.

?The cost to drill incremental wells comes down a lot,? he said. ?We have several instances where we have two or three wells on one location.?

That could rise to eight or 12 wells drilled on one pad site. And at the same time, fracking prices are coming down because companies are getting better at it and faster. ?We like the way the metrics are lining up,? Hart said.

Howard said not everyone has been quick to embrace the idea of drilling horizontally in other formations. ?Our industry is bad about seeing the forest for the trees. They get hung up on the Eagle Ford,? Howard said.

?If it doesn't start with an E and spell Eagle Ford, they're not interested.?

But not all the formations are created equal, and Howard said not all these newer plays will be profitable. Thomas Tunstall, a professor at the University of Texas at San Antonio, said the one thing that's certain about the industry is change.

?You have to be careful of these shale maps,? said Tunstall, who in presentations likes to show a 2009 map of U.S. shale plays, which doesn't include what now appear to be two of the country's most productive fields in Texas and North Dakota.

?It didn't have the Eagle Ford or the Bakken on it at all.?

jhiller@express-news.net

Twitter: @Jennifer Hiller

Star Trek: The Original Series Carlton Morgan Freeman Dead Stand Up to Cancer Azarenka NFL fantasy football Chris Kluwe

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.